Helicobacter Pylori, an intricate host

By: Dr. Natalia Loaiza Díaz, M.D.

Medical Microbiologist, Clinical Pathology Leader. Clinical Hematological Laboratory S.A.S.

Published: April 25, 2023

For centuries it was thought that the stomach, due to its acidic environment, was protected against infections. Today it is known that more than half of the world’s population harbors a bacterium, Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori), which with the help of a kind of tail (composed of a group of four to eight flagella) is able to swim to the mucosa of the stomach to live there for years.

- pylori was discovered in the early 1980s by Australian researchers Barry J. Marshall and J. Robin Warren in samples of gastric mucosa, who in 2005 were awarded the Nobel Prize in Physiology and Medicine after proving the causal relationship between the bacterium and gastric ulcers.

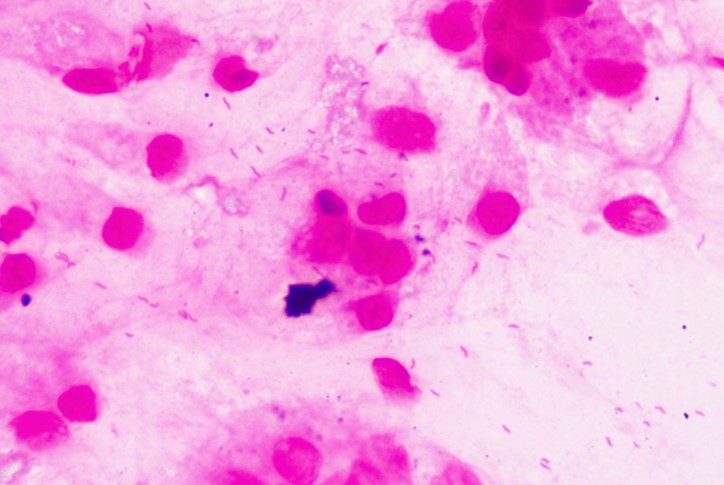

Figura 1. Helicobacter pylori en biopsias gástricas con coloración de Gram. Microscopía de luz, 100 x. Archivo de imágenes Laboratorio Clínico Hematológico S.A.S., Medellín, Colombia.

Figura 2. Colonias de Helicobacter pylori en agar Brucella a partir de biopsias gástricas. Archivo de imágenes Laboratorio Clínico Hematológico S.A.S. Medellín, Colombia.

¿How common is colonization or infection with H. pylori?

In developing countries between 70% and 90% of the population lives with H. pylori since childhood. In industrialized countries the prevalence is lower, 40% or less, due to better hygiene and environmental sanitation conditions, and to the use of treatment in people colonized with the bacteria.

In Colombia, it has been suggested that 70% to 80% of the population is infected with this microorganism; however, these percentages seem to vary significantly between regions. In 2003, Bravo et al. found that the national prevalence was 69.1% (65.4% on the Atlantic coast, 69.5% in the Andean region, 85.5% in Manizales and 99.1% in Tunja). Subsequent studies found lower prevalences of infection in other cities (36.4% in Medellin and 38.5% in Cali).

¿How does H. pylori reach the stomach?

Factors such as overcrowding, poor hygienic conditions, lack of access to clean water and consumption of water and food contaminated with feces favor contact and infection of people with H. pylori from the first years of life. This can also occur in a healthy person through direct contact with saliva or other body fluids from an infected person, usually a close relative such as a mother, father or grandmother.

H. pylori enters the body through the mouth and, once ingested, lodges in the stomach, being able to survive its acidic and hostile environment for years, while causing inflammation and alterations in the wall of this organ. To achieve this feat, it uses an arsenal of tools that allow it to quickly locate itself in the stomach wall, camouflage itself, evade the immune response and create a microenvironment that guarantees its survival there for a long time.

¿How does H. pylori ensure its stay in the stomach?

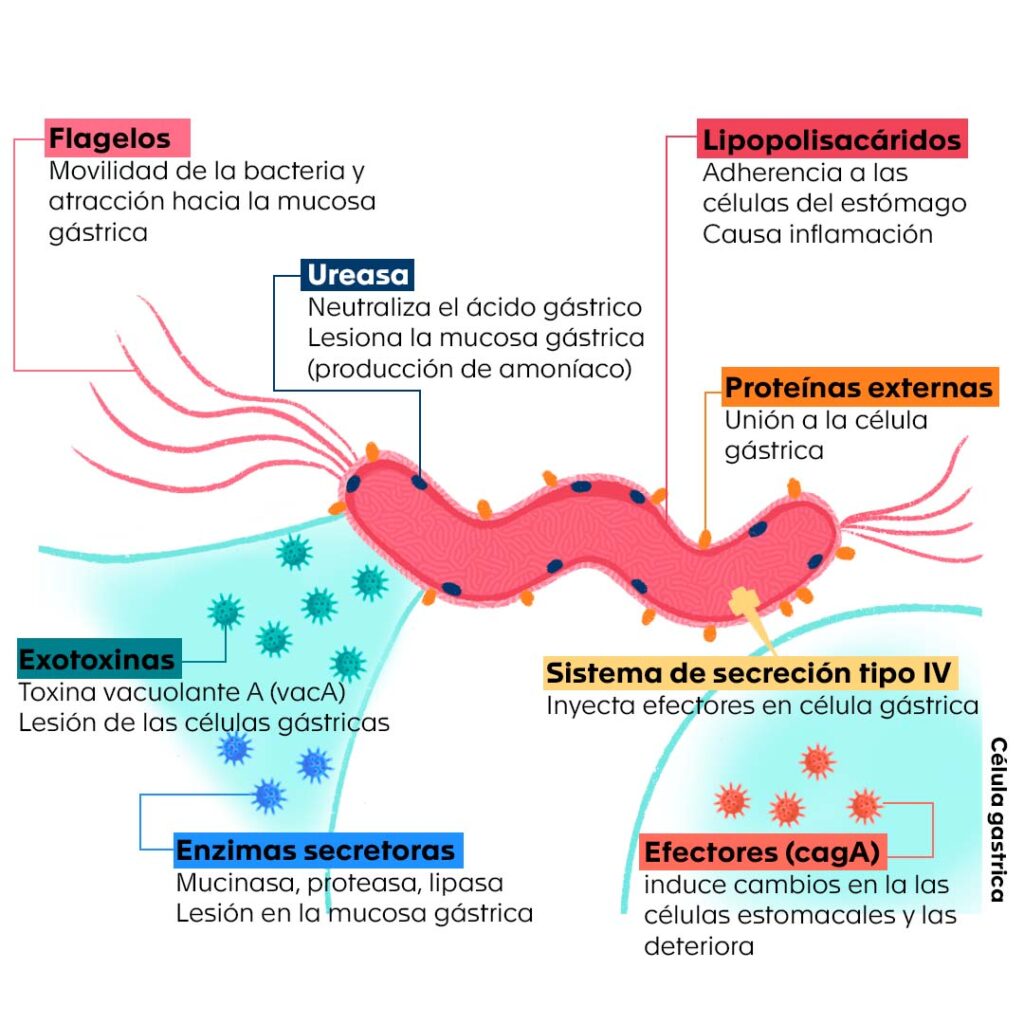

Some of the tools used by H. pylori to ensure its stay in an appropriate and comfortable place in the stomach (Figure 3) are: : 2,5,14-16

- A group of mobile tails or flagella in its structure, with which it moves over the stomach to locate itself in one of its layers, the mucosa.

- Receptors of chemical signals generated in the presence of components such as mucin, sodium bicarbonate, urea, sodium chloride, among others, present in the stomach, which favor the movement and colonization of the bacteria in this organ.

- Production of enzymes such as urease and hydrogenase. The former moderates the pH of the stomach by promoting the decomposition of urea into ammonia and bicarbonate; it also favors the damage of gastric cells and promotes the local inflammatory response by cells of the immune system of the infected person. The second allows it to use hydrogen as an energy source.

- Adhesion proteins that interact with receptors located on the surface of gastric cells, allowing the bacteria to latch onto them and, from there, release signals to promote the aforementioned local inflammation.

- CagA, a protein that induces changes in the shape and polarity of stomach cells and deteriorates them.

- VacA, a protein that promotes the formation of vacuoles or acid bubbles inside gastric cells, altering their structures and destroying them. In addition, it modulates the response of the immune system, which facilitates the permanence of the bacteria in the gastric mucosa.

- DupA, a protein that gives the bacteria high resistance to acidity and stimulates the production of inflammatory components such as interleukin 8 (IL-8), which leads to site invasion by polymorphonuclear immune system cells.

- OipA, another protein that is on the outside of the microorganism wall and supports its adherence to the stomach mucosal cells and the generation of inflammation.

- GGT, an enzyme that leads to the division cycle or functioning of the infected gastric cell to stop and eventually terminate it.

With H. pylori lodged and comfortable in the stomach, these and other tools work to perpetuate the infection, inflammation and tissue damage, favoring the development of gastritis. Not in all cases does the bacterium have all of the above-mentioned weapons; however, the presence of some of them makes it more virulent, i.e., more aggressive and more likely that the infection will progress to ulcer and then to stomach cancer 5,14-16

¿How does H. pylori infection affect us?

Most infected persons have no symptoms; however, H. pylori is considered the main factor associated with gastritis and peptic ulcer in the world, in which pain or burning is felt in the upper abdomen (the epigastrium) and which may or may not be accompanied by nausea, vomiting, a feeling of fullness or loss of appetite. Among infected persons with chronic gastritis, 10% to 15% develop peptic ulcer, with H. pylori being responsible for 85% of gastric ulcers and 95% of duodenal ulcers.

According to the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), infected individuals have a two to six times higher risk of developing gastric cancer of the adenocarcinoma and mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue lymphoma (MALT) type than uninfected individuals.

Although the passage from gastritis to ulcer, to gastric or MALT cancer, etc. is not immediate, it is a long and sustained process over time1, we must pay attention to it and strive to prevent it, since gastric adenocarcinoma continues to be the third leading cause of death from cancer in Colombia, with a mortality reported for 2018 of 11.36%. The presence of H. pylori in humans has also been related to pathologies of other organs such as the esophagus, intestine, liver, pancreas, among others.

In the Hematológico

At Hematológico we have non-invasive diagnostic and follow-up tests performed on high-tech platforms, as well as standardized techniques for cytopathological analysis, culture, identification and susceptibility testing from gastric tissue samples, and a specialized medical team in both the areas of Microbiology and Anatomic Pathology, to ensure timely, accurate and integrated diagnoses, and to be an ally of gastroenterologists and endoscopists in the management of their patients.

Bibliography

- Santos MLC, de Brito BB, da Silva FAF, Sampaio MM, Marques HS, Oliveira E Silva N, et al. Helicobacter pylori infection: Beyond gastric manifestations. World J Gastroenterol. el 28 de julio de 2020;26(28):4076–93.

- de Brito BB, da Silva FAF, Soares AS, Pereira VA, Santos MLC, Sampaio MM, et al. Pathogenesis and clinical management of Helicobacter pylori gastric infection. World J Gastroenterol. el 7 de octubre de 2019;25(37):5578–89.

- Abbott A. Medical Nobel awarded for ulcers. Nature. el 3 de octubre de 2005;news051003-2.

- Pajares JM, Gisbert JP. Helicobacter pylori: its discovery and relevance for medicine. Rev Esp Enfermedades Dig [Internet]. octubre de 2006 [citado el 5 de abril de 2023];98(10). Disponible en: http://scielo.isciii.es/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S1130-01082006001000007&lng=en&nrm=iso&tlng=en

- Murray PR, Rosenthal KS, Pfaller MA. Medical microbiology. Ninth edition. Edinburgh ; New York: Elsevier; 2021. 855 p.

- Hooi JKY, Lai WY, Ng WK, Suen MMY, Underwood FE, Tanyingoh D, et al. Global Prevalence of Helicobacter pylori Infection: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Gastroenterology. agosto de 2017;153(2):420–9.

- Rupnow M. A Dynamic Transmission Model for Predicting Trends in Helicobacter pylori and Associated Diseases in the United States. Emerg Infect Dis. junio de 2000;6(3):228–37.

- Bayona Rojas MA, Gutiérrez Escobar AJ. Helicobacter Pylori: Vías de transmisión. Medicina (Mex). el 22 de septiembre de 2017;39(3):210–20.

- Otero R W, Trespalacios R AA, Otero P L, Vallejo O MT, Torres Amaya M, Pardo R, et al. Guía de práctica clínica para el diagnóstico y tratamiento de la infección por Helicobacter pylori en adultos. Rev Colomb Gastroenterol. 2015;30:17–33.

- Bravo LE, Cortés A, Carrascal E, Jaramillo R, García LS, Bravo PE, et al. Helicobacter pylori: patología y prevalencia en biopsias gástricas en Colombia. Colomb Médica. el 10 de noviembre de 2003;34(3):124–31.

- Correa G S, Cardona A AF, Correa G T, Correa L LA, García G HI, Estrada M S. Prevalencia de Helicobacter pylori y características histopatológicas en biopsias gástricas de pacientes con síntomas dispépticos en un centro de referencia de Medellín. Rev Colomb Gastroenterol. 2016;31:9–15.

- Sepulveda Copete M, Maldonado Gutiérrez C, Bravo Ocaña JC, Satizabal N, Gempeler Rojas A, Castro Llanos AM, et al. Prevalencia de Helicobacter pylori en pacientes llevados a endoscopia de vías digestivas altas en un hospital de referencia en Cali, Colombia, en 2020. Rev Colomb Gastroenterol. el 21 de diciembre de 2022;37(4):355–61.

- Kayali S, Manfredi M, Gaiani F, Bianchi L, Bizzarri B, Leandro G, et al. Helicobacter pylori, transmission routes and recurrence of infection: state of the art. Acta Bio Medica Atenei Parm. el 17 de diciembre de 2018;89(8-S):72–6.

- Chmiela M, Kupcinskas J. Review: Pathogenesis of Helicobacter pylori infection. Helicobacter. septiembre de 2019;24 Suppl 1(Suppl Suppl 1):e12638.

- Elizalde JI. Patogenia de la infección por Helicobacter pylori. Gastroenterol Hepatol Contin. 2004;3(6):256–61.

- Guevara B, Cogdill AG. Helicobacter pylori: A Review of Current Diagnostic and Management Strategies. Dig Dis Sci. julio de 2020;65(7):1917–31.

- Connor BA. Chapter 4. Travel-Related Infectious Diseases: Helicobacter pylori. En: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Brunette GW, editores. CDC yellow book 2020: health information for international travel. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 2019.

- Muñoz MS, Valle Rossi ML, Ferrer L, Medeot R, Herrera Najum P, López L, et al. Utilidad del antígeno de Helicobacter pylori en heces como método diagnóstico no invasivo. Acta Gastroenterológica Latinoam. 2019;49(1):22–31.

- Sanchez Londoño S, Guevara Casallas G, Niño S, Arteta Cueto A, Marcelo Escobar R, Camilo Ricaurte J, et al. Patrones de detección de Helicobacter pylori y lesiones relacionadas mediante protocolo Sydney en una población de Antioquia, Colombia. Rev Gastroenterol Perú. el 30 de junio de 2022;42(2):86.