Hepatitis virales

Viral Hepatitis

By: Ana Isabel Toro-Montoya*, Juan Carlos Restrepo-Gutiérrez**. *Bacteriologist and Clinical Laboratorist. MSc in Virology. Scientific Director, Editora Médica Colombiana S.A. Medellín, Colombia. **Doctor, Specialist in Internal Medicine, Specialist in Clinical Hepatology, MSc, PhD. Professor, Universidad de Antioquia. Coordinator of the Hepatology Unit and Liver Transplant Program, Pablo Tobón Hospital Pablo Tobón Uribe Hospital. Medellín, Colombia. Published on 27-07-2021

Compartir

The term “hepatitis” means inflammation of the liver. Hepatitis is usually caused by viral infections, however, some medications, toxins, chronic alcohol consumption, and diseases such as autoimmune diseases can also be the cause. Viral hepatitis is a worldwide public health problem. There are several viruses associated with this disease, but the most common are hepatitis A virus, hepatitis B virus and hepatitis C virus. Other viruses that can cause liver inflammation include hepatitis D (delta) virus, Epstein-Barr virus, herpes simplex virus and cytomegalovirus.

Although hepatitis can be caused by different viruses, with different routes of transmission, the liver is affected in one way or another, either because the virus directly infects liver cells (hepatocytes) for replication, or because hepatitis occurs as part of a generalized infection in the body. The infection can be acute or chronic depending on its duration, and the host immune response is usually responsible for liver damage. Hepatitis B and C viruses cause most chronic infections, which can eventually lead to liver damage so severe that liver transplantation is necessary. The most common hepatitis A, B and C are described below.

Hepatitis A

Hepatitis A is the most frequent hepatitis presentation in the world and is one of the notifiable diseases in Colombia. Epidemiological observations associate it to temperate zones and underdeveloped countries due to the precarious sanitary measures; in addition, it is presented as epidemics that recur cyclically. Hepatitis A is caused by a non-enveloped RNA virus, belonging to the Picornaviridae family, inactivated by ultraviolet light, boiling and contact with chlorine or formaldehyde.

Hepatitis A virus is usually transmitted by ingestion of water and food contaminated with fecal material from an infected individual. The incubation period is between 2 and 4 weeks. More than 75% of adults with hepatitis A have predominantly gastrointestinal symptoms, such as nausea, abdominal pain, lack of appetite, diarrhea, fever, fatigue, and jaundice (yellowing of the skin and eyes). In contrast, most children with the disease are asymptomatic, and it leads to the formation of protective antibodies. Mortality from hepatitis A is generally considered to be very low.

For the diagnosis of hepatitis A, a serum antibody test can detect the presence of immunoglobulin (Ig) type M (IgM), which confirms current or recent infection. Similarly, IgG antibodies can be detected if confirmation of past or resolved exposure to hepatitis A virus is desired. These IgG antibodies are also positive in vaccinated persons.

To prevent hepatitis A, particularly for travelers to endemic areas, inactivated and attenuated virus vaccines are available. Some endemic countries have included the vaccine in their vaccination schedules for children; it is safe and capable of producing neutralizing antibodies in more than 94% of cases after the first dose. Other people who may benefit from the vaccine are patients awaiting liver transplantation, those using illicit intravenous drugs, homosexuals, and those receiving clotting factor concentrates. The duration of effect of the vaccine is estimated to be up to 20 years. Individuals who have already been exposed to the virus can receive gamma globulin against hepatitis A virus to prevent the disease. It should also be kept in mind that effective measures for the prevention of hepatitis A include avoiding fecal contamination of hands, water and food to prevent transmission of the virus.

Hepatitis B

It is estimated that at least 2 billion people have been exposed to the hepatitis B virus, and more than 300 million of them are chronic carriers. Hepatitis B virus is made up of DNA and belongs to the Hepadnaviridae family; this family of viruses, although infecting hepatocytes, can be found in other organs such as the kidney and pancreas; however, infection in these sites does not result in extrahepatic disease.

Hepatitis B virus has vertical transmission, that is, from mother to child during childbirth, but it is also transmitted through sexual contact, through the use of intravenous illicit drugs if needles are shared, through tattoos and piercings, in persons undergoing frequent hemodialysis and through occupational accidents. The incubation period can range from 30 to 180 days, and most infected individuals are able to clear the infection spontaneously. A small percentage remain carriers of the virus and some of them develop chronic hepatitis, which may eventually progress to cirrhosis or even liver cancer. The age at which infection is acquired is the main risk factor for the development of chronic infection. Children infected in the first 6 years of life are at higher risk for chronic infection.

As is common for some viral hepatitis, acute infection is asymptomatic in most infected individuals, but clinical manifestations such as fever, jaundice, dark urine, extreme fatigue, nausea, vomiting and abdominal pain may occur. Hepatitis B virus can be detected in blood, semen, vaginal secretions, saliva and even in tears in small amounts.

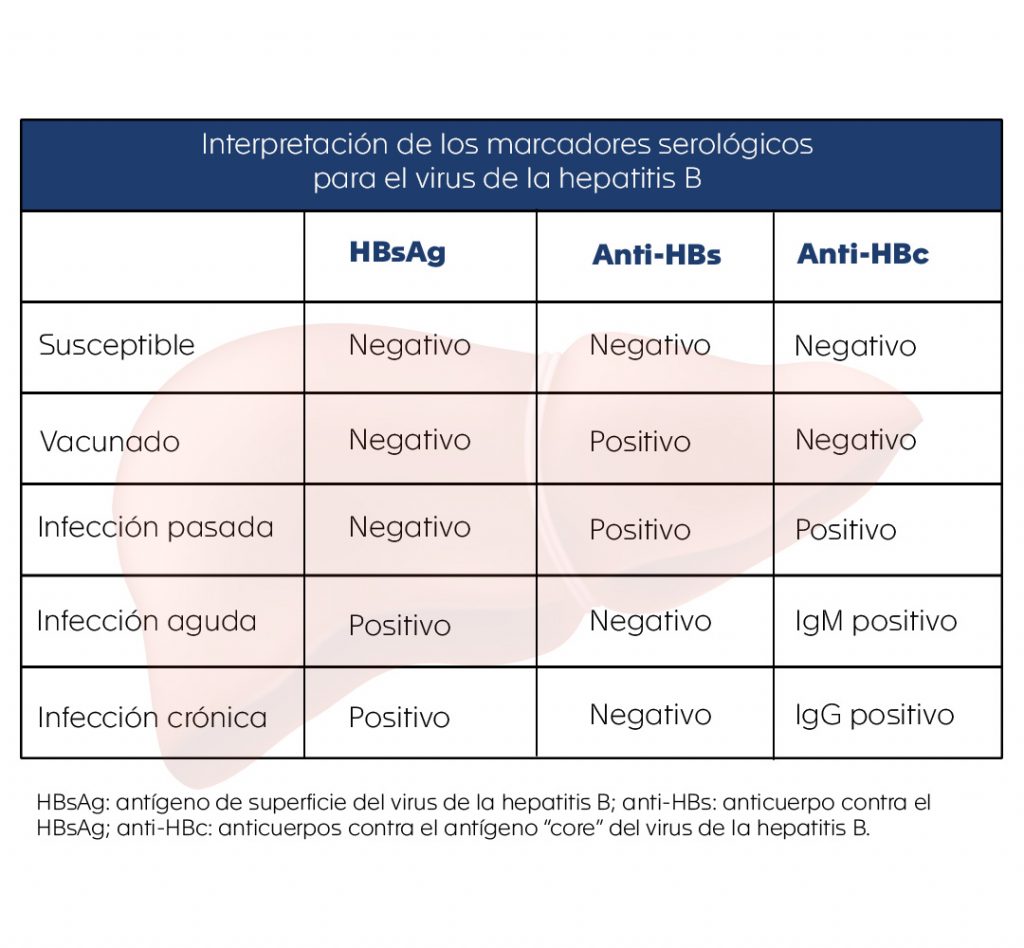

For the diagnosis of hepatitis B, there are several serological markers that reflect the type of infection a person has. These serological markers can be detected in the blood of infected individuals and provide valuable information regarding the status of their infection and help the physician to determine the management and treatment of the disease. To better understand the usefulness of the main serological markers found in the blood of infected individuals and the information they provide (see table), the following questions are posed:

¿Is the patient infected with this virus?

To answer this question, a request for hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg) is essential. It is usually detected in serum from the fourth week after contact with the virus, and even before the onset of symptoms.

¿Does the patient have an acute or chronic infection?

In this instance, detection of antibodies against the hepatitis B virus core antigen (HBcAg) is useful. Its blood levels rise one to two weeks after HBsAg becomes positive.

The detection of IgM and IgG against HBcAg is very useful to differentiate the type of infection. IgM indicates an acute or recent infection, while the presence of IgG indicates a chronic infection, since these antibodies appear positive 3 to 6 months after infection and generally remain positive for the life of the infected individual. HBsAg also remains positive during chronic infection.

¿How to know if the patient has immunity to hepatitis B virus?

Here it is useful to request tests that detect antibodies against hepatitis B virus (anti-HBs and anti-HBc), which are positive in two contexts:

- In the patient who received the vaccine. In these cases, anti-HBs is positive and anti-HBc is negative.

- In the patient who presented the infection and acquired immunity against the virus. In these cases, both anti-HBs and anti-HBc are positive.

¿How do you know if a person is susceptible to infection with the virus?

In these cases, the HBsAg, anti-HBs and anti-HBc are all negative, indicating that the individual has not been exposed to the virus and can become infected.

To assess the status of patients who have already been infected with the virus, a molecular test that quantifies viral DNA (viral load) is also available.

For the prevention of infection there are several vaccines, which have proven to be highly effective. Hepatitis B is a potentially preventable disease if the vaccine is given as part of vaccination programs. The 3-dose vaccination schedule should ideally be initiated in all infants as soon as possible after birth.

Hepatitis C

Hepatitis C virus was initially known as “non-A non-B” virus. With the development of molecular tests, its genome (genetic material) was identified, characterizing it as an RNA virus, belonging to the Flaviviridae family. The incidence is higher between 30 and 49 years of age, and although it has decreased, it is still considered by the World Health Organization (WHO) as one of the main health problems in the world. An estimated 71 million people are chronically infected with hepatitis C virus.

Prior to 1992, hepatitis C had a major public health impact because of the risk of transmission of the virus from infected donor blood. Routine testing is now performed in blood banks to ensure the safety of transfusions of blood and blood derivatives. The main routes of transmission of the virus are through sexual contact, inappropriate use of illicit intravenous drugs where needles are shared, tattoos, piercings, infections in dialysis units and exposure due to occupational risk, such as accidents with needles contaminated by the virus.

The incubation period is about 8 weeks. Unlike hepatitis B virus infections, most hepatitis C virus infections do progress to the chronic phase, and as with hepatitis B, can progress to liver cirrhosis and eventually liver cancer. From the clinical point of view, hepatitis C has been considered a silent disease with few clinical manifestations; however, in 20% of cases the common symptoms of hepatitis, such as abdominal pain, vomiting, fever, fatigue, etc., may be present.

The initial diagnosis is made by looking for antibodies against the hepatitis C virus, but this test will eventually need a molecular confirmatory test, since the presence of antibodies does not differentiate between persons with an active infection and those with a resolved past infection.

Other studies for the evaluation of patients with hepatitis C include determination of viral load and genotyping of the virus, which are reserved for therapeutic decisions.

Laboratorio Clínico Hematológico

In the Hematológico we have tests for the detection of serological markers of hepatitis B (HBsAg, Anti-HBs, Anti-HBc), antibodies against hepatitis C virus (anti-HCV), IgM and total antibodies against hepatitis A virus, and others to support the laboratory diagnosis of viral hepatitis.

Bibliography

- Lanini S, Ustianowski A, Pisapia R, Zumla A, Ippolito G. Viral hepatitis: etiology, epidemiology, transmission, diagnostics, treatment, and prevention. Infect Dis Clin North Am. 2019 Dec;33(4):1045-1062. doi: 10.1016/j.idc.2019.08.004. PMID: 31668190.

- Zarrin A, Akhondi H. Viral hepatitis. [Updated 2021 Apr 7]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2021 Jan. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK556029/.

- Razavi H. Global epidemiology of viral hepatitis. Gastroenterol Clin North Am. 2020 Jun;49(2):179-189. doi: 10.1016/j.gtc.2020.01.001. PMID: 32389357.

- Prasidthrathsint K, Stapleton JT. Laboratory diagnosis and monitoring of viral hepatitis. Gastroenterol Clin North Am. 2019 Jun;48(2):259-279. doi: 10.1016/j.gtc.2019.02.007. Epub 2019 Apr 1. PMID: 31046974.

- Abutaleb A, Kottilil S. Hepatitis A: epidemiology, natural history, unusual clinical manifestations, and prevention. Gastroenterol Clin North Am. 2020 Jun;49(2):191-199. doi: 10.1016/j.gtc.2020.01.002. Epub 2020 Mar 29. PMID: 32389358; PMCID: PMC7883407.

- Restrepo Gutiérrez JC, Toro Montoya AI. Hepatitis A. Med. Lab. 2011;17(1-2):11-2. https://medicinaylaboratorio.com/index.php/myl/article/view/320.

- Mehta P, Reddivari AKR. Hepatitis. [Updated 2021 Jan 16]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2021 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK554549/.

8. Escandón-Felizzola VD. Recomendaciones en el tratamiento actual de la infección crónica por el virus de la hepatitis B. Hepatología 2020;1:36-54. https://doi.org/10.52784/27112330.114.

9. Toro Montoya AI, Restrepo Gutiérrez JC. Hepatitis B. Med. Lab. [Internet]. 1 de julio de 2011 [citado 10 de julio de 2021];17(7-8):311-29. Disponible en: https://medicinaylaboratorio.com/index.php/myl/article/view/360.

10. Trépo C, Chan HL, Lok A. Hepatitis B virus infection. Lancet. 2014 Dec 6;384(9959):2053-63. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)60220-8. Epub 2014 Jun 18. PMID: 24954675.

11. Seto WK, Lo YR, Pawlotsky JM, Yuen MF. Chronic hepatitis B virus infection. Lancet. 2018 Nov 24;392(10161):2313-2324. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)31865-8. PMID: 30496122.

12. OMS. Hepatitis B. https://www.who.int/es/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/hepatitis-b.

13. Restrepo Gutiérrez JC, Toro Montoya AI. Hepatitis C. Med. Lab. 2011;17(9-10):411-28. https://medicinaylaboratorio.com/index.php/myl/article/view/368.

14. Spearman CW, Dusheiko GM, Hellard M, Sonderup M. Hepatitis C. Lancet. 2019 Oct 19;394(10207):1451-1466. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(19)32320-7. PMID: 31631857.

15. Marín-Zuluaga JI, Díaz-Ramírez GS. Tratamiento actual de la hepatitis C en Colombia. Hepatología 2020;1:99-115. https://doi.org/10.52784/27112330.119.